By BCD marketplace partner Crisis24

Overview

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season is forecast to be very active, putting tens of millions of lives at risk and potentially causing billions of dollars in damage across coastal areas of southern and eastern US due to possible flooding, damaging winds, and storm surges. This season has the potential to be one of the most active in history. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has forecast 17-25 named storms, the largest number ever predicted since forecasts began in 2010, and significantly above the historical average of 14. The main factors for the active Atlantic storm season are abnormally high sea temperatures and the likely transition to the La Niña climate pattern June-September, both of which will likely aid in the more frequent development of storms and increase the potential for systems to intensify rapidly.

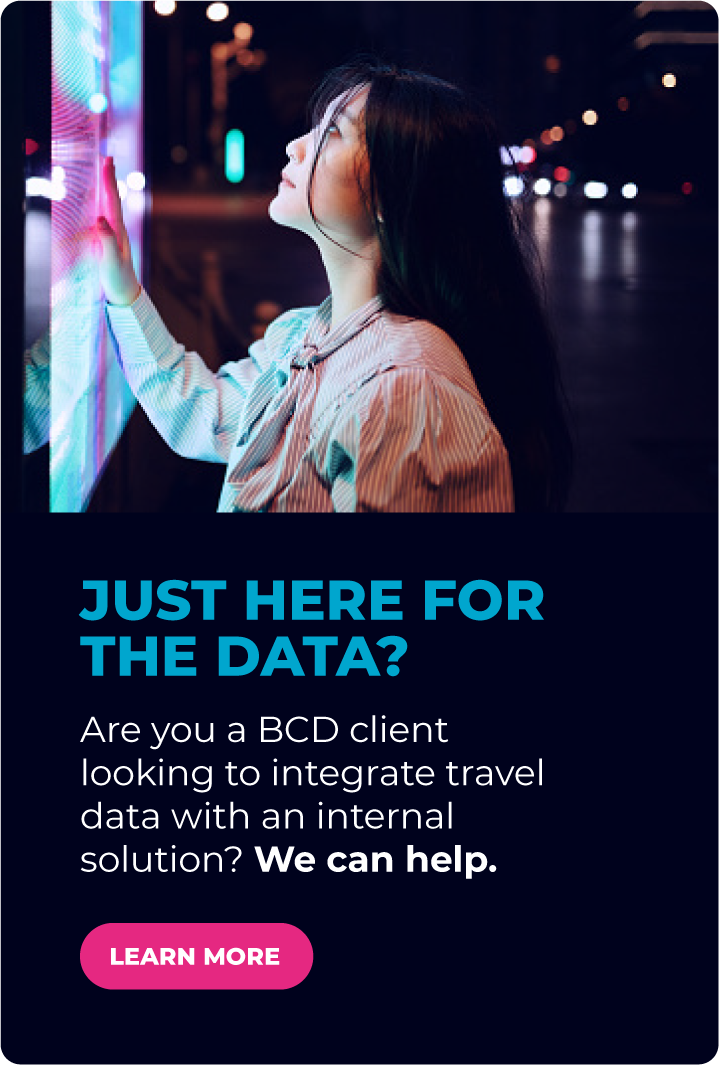

The Atlantic and central Pacific hurricane seasons run from June 1 through Nov. 30, with the eastern Pacific season running May 15 through Nov. 30; however, storms can form outside the official seasonal windows. The Atlantic hurricane season has a relatively defined peak August-October, with the eastern and central Pacific basins having a less defined peak July-September. The storm systems that form vary greatly in intensity and track and have the potential to impact a wide-ranging area of Central and North America. Storms in the eastern Pacific can generally impact anywhere from the Pacific coasts of Central America northwards along the west coast of Mexico and reaching the southwest coast of the US. Atlantic storms’ range of impact extends from northwestern South America through Central America, eastern Mexico, the Caribbean, and the southeastern US northwards along the east coast to the Atlantic Maritimes in Canada. Outlying islands in both the Pacific and Atlantic, such as Hawaii and the Azores, can be impacted by storms; however, direct landfall is rare. Storm systems generally weaken upon landfall, making coastal areas the most at-risk. However, some systems can continue to track inland with varying intensities and bring adverse conditions to places far from the coast.

Image 1 – Paths of previous hurricanes and named storms in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific basins

The primary hazard from tropical systems is flooding caused by both storm surge (an abnormal rise in coastal or riverine waters caused by storm winds) and periods of heavy rainfall associated with the storms. Strong winds can also cause property damage, whip up dangerous flying debris as the storm passes, and generate rough seas that pose a threat to mariners and coastal residents. Tornadoes can also occur when storms make landfall.

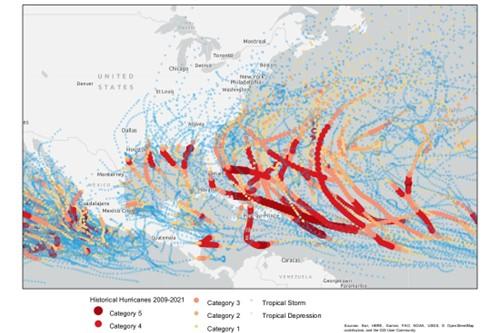

Hurricanes are usually measured using the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (see Image 2), which categorizes hurricanes from 1 to 5 based on wind speed. Major hurricanes are generally classed as being Category 3 or above. While the scale can be used to gauge the expected level of wind damage the hurricane may cause, it does not take into account other environmental hazards such as storm surge, rainfall, and tornadoes. The intensity of a storm is not the only factor in determining the likely extent of its impact, with other factors also having a major influence. For example, a slow-moving storm, regardless of its intensity, has the potential to produce lingering showers over a particular region, which may be more impactful than a higher intensity storm that passes rapidly through an area. Additionally, the relative vulnerability and preparedness of the location struck by the storm can have a great bearing on the level of damage and disruptions caused. For instance, due to limited resources and constraints in assistance reaching the population in need, some isolated islands in the Caribbean may be more heavily impacted by relatively minor storms than coastal areas of the US. If an island only has one airport or port and these are damaged during the storm it restricts their ability to receive aid.

Image 2 – Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale

2024 Outlook

Forecasters take into account a combination of climatic indicators, including sea surface temperatures and the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) weather pattern, and compare these to previous historical trends to formulate a probabilistic assessment of the likely level of tropical cyclone activity for the upcoming season. Warmer sea surface temperatures provide conditions more favorable for tropical systems to form. La Niña weather patterns tend to favor stronger activity in the Atlantic basin and suppress activity in the Pacific basins. Conversely, an El Niño pattern suppresses activity in the Atlantic basin and enhances it in the Pacific basins. Forecasters are unable to provide early accurate predictions of precisely where hurricanes and other storms systems are likely to make landfall each season as the track of each particular storm system is determined by the specific weather conditions present during the formation and passage of the storms; however, some estimates can be gauged on the number of storms expected in a relatively wide geographical area based on the predicted level of activity during the season and the comparison to historical seasons, as well as taking other environmental factors into account.

Headlines

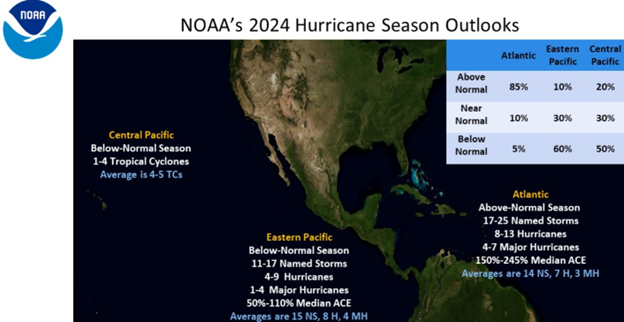

As depicted in Image 3, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has predicted the following hurricane activity levels across the Atlantic, eastern Pacific, and central Pacific basins for 2024:

- Atlantic: Above-Normal Season Likely

- Eastern Pacific: Below-Normal Season Likely

- Central Pacific: Below-Normal Season Likely

Image 3 – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2024 Hurricane Season Outlooks

Atlantic Basin

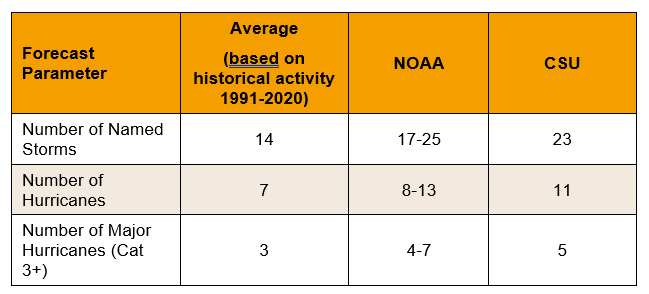

NOAA’s outlook for the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season indicates an above-average season is most likely. The outlook has forecast a 85-percent chance of an above-normal season, a 10-percent chance of a near-normal season, and a 5-percent chance of a below-normal season. There is a 70-percent probability of the season having 17-25 named storms, including eight to 13 hurricanes and four to seven major hurricanes. The basis for this outlook is due to warmer sea-surface temperatures and weaker trade winds in the Atlantic Hurricane Main Development Region (MDR) in the tropical North Atlantic and Caribbean Sea, weaker vertical wind shear, an enhanced West African Monsoon, and a likely La Niña weather pattern during the hurricane season. Models indicate a 77-percent likelihood of a La Niña event, as opposed to a 22-percent chance of an ENSO-neutral event and a negligible 1-percent chance of an El Niño event. Along with NOAA, other respected forecasters are generally predicting a slightly higher number of named storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes than during an average hurricane season (see Table 1). As with most Atlantic hurricane seasons, the majority of the activity is expected to occur during the peak months of August, September, and October.

Table 1 – 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast

Colorado State University (CSU) has produced some probabilities of the likelihood of hurricanes making landfall over particular areas in their extended-range forecast for the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season. CSU has forecast a 44-percent probability of at least one major hurricane (Category 3 or above) making landfall on the US East Coast, including the Florida Peninsula, and a 25-percent chance on the Gulf Coast (compared to historical averages of 29 and 16 percent respectively). CSU has also predicted a 30-percent probability of a major hurricane tracking into Mexico (the seasonal average for the last century is 19 percent) and a 46-percent probability of a major hurricane tracking into Mexico (the seasonal average for the last century is 30 percent). AccuWeather has predicted four to six named storms will directly impact the US during the season, compared to a historical average of four.

See Part 2 for Eastern Pacific, Central Pacific, Impact of Hurricanes, and Preparation Measures

Interested in exploring Travel Risk Management solutions? Click Here »